Eloquently written letters were part of Victorian era courtship, and continued even after a couple’s marriage.

Today, no form of communication is more important, more romantic—and more in danger of being lost—than the written word. Text-messaging has unfortunately taken over as the number one way to communicate, but that doesn’t mean we can’t learn something from the beautiful and elegant writings of the past.

Letters written during the Civil War era often contained accounts of battles, life in camp, and general news, but many—even the ones penned by historical figures that we think of as strong, unemotional, and intrepid—are sweet, poignant, and heartfelt missives to their loved ones at home.

In this post I’m going to cover a few of the heartwarming stories of everlasting love that I stumbled upon while doing research for my first Civil War novel Shades of Gray. In the midst of the chaos of today’s society, it may be hard to imagine the type of devotion that plays out in these letters.

One would not expect, after all, to hear sweet murmurings of love from some of the most renowned soldiers to come out of the war—warriors with names like J.E.B. Stuart, Stonewall Jackson and George Pickett, to name a few.

With Valentine’s Day coming next week, I hope you enjoy these words of love as much as I do, and that you can appreciate the beautiful use of the English language, written in a way that brings the emotions of the past back to life.

Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson

Over the years, the persona of Stonewall Jackson has attained almost mythical proportions. In life, they say he was almost impossible to know. In death, he became even more of an enigma because he was such a legendary leader.

Anyone who has read anything about this mysterious, brave, bold, respected and feared commander will find these tender-hearted love letters incredible.

The following letters and reminiscences are taken from the book, “Life and Letters of Stonewall Jackson,” which was written by his wife, Mary Anna Jackson.

“Sept. 25, 1862

Darling, my heart turns to you with a love so great that pain flows in its wake. You cannot understand this, my beautiful, bright-eyed, sunny-hearted princess. Your face is the sweetest face in all the world, mirroring, as it does, all that is pure and unselfish, and I must not cast a shadow over it by the fears that come to me, in spite of myself. No, a soldier should not know fear of any kind. I must fight and plan and hope, and you must pray. Pray for a realization of all our beautiful dreams, sitting beside our own hearthstone in our own home—you and I, you my goddess of devotion, and I your devoted slave. May God in his mercy spare my life and make it worthy of you!…

Your soldier”

And here is an excerpt from another letter, written three months before the well-known Battle of the Wilderness. In it he tells of denying a furlough to one of his men, while setting an example by staying at his post of duty—despite the hardships.

“Feb. 3, 1863

In answer to the prayers of God’s people, I trust He will soon give us peace. I haven’t seen my wife for nearly a year—my home in nearly two years, and have never seen our darling little daughter; but it is important that I, and those at headquarters, should set an example of remaining at the post of duty.”

According to his wife, Jackson did finally get to see his daughter when she was five months old.

“It was raining and he was afraid to take her in his arms with his wet overcoat, but upon arrival at the house, he speedily divested himself of his overcoat, and, taking his baby in his arms, he caressed her with the tenderest affection, and held her long and lovingly. During the whole of this short visit when he was with us, he rarely had her out of his arms, waking her, and amusing her in every way that he could think of—sometimes holding her up before a mirror and saying, admiringly, “Now, Miss Jackson, look at yourself.” Then he would turn to an old lady of the family and say, “Isn’t she a little gem?” When she slept in the day, he would often kneel over her cradle, and gaze upon her little face with the most rapt admiration, and he said he felt almost as if she were an angel in her innocence and purity.”

General Jackson was accidentally shot by his own troops at the Wilderness on May 2, 1863. He lost his left arm, but it was thought that he would recover. Unfortunately, there were complications and he died of complications eight days later, most likely from pneumonia.

His last words were:

“Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

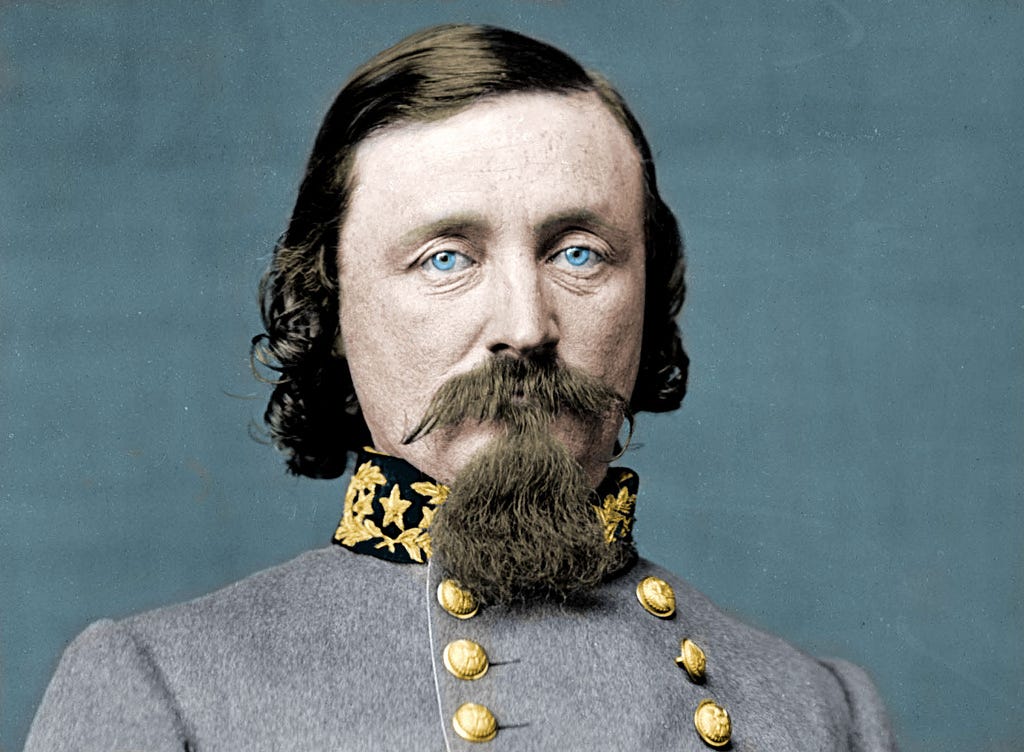

General George Pickett

Most people probably don’t know about Pickett’s tragic life off the battlefield or the fact that he was married three times (four times if you count being married in two different ceremonies to the same woman). His life also involved a poignant love story that continued after his death.

Pickett met his first wife, Sally Harrison Ming, while at West Point, and eventually married her after coming back from serving in the war with Mexico. Said to be madly in love, Pickett was excited to find that Sally was pregnant—but he was devastated when both Sally and the child died during the birth. Pickett stayed in Virginia for six months before returning to the Army where he requested a post on the frontier.

It was during this short time in Virginia that he met La Salle Corbell, daughter of Dr. John Corbell. Pickett was 23 years her senior (She was only eight and he in his 30s). But as La Salle would later write in her memoirs, she fell instantly in love and swore she would never love another man.

When Pickett was posted on peacekeeping duties between the Americans and the Indians, he met and fell in love with an Indian Princess. Here is where he was married twice to the same woman, first in the traditional Indian ceremony, and later in a ceremony in the home of a local businessman.

His Indian wife bore him a son, James Tilton Pickett, but the young mother never fully recovered from a difficult delivery and died shortly after. Needless to say, Pickett was inconsolable with grief. Reassigned to the West, he gave up the care of the child to his Indian grandmother.

George had been corresponding with La Salle Corbell, and finally married the 16-year-old during the Civil War. George and La Salle had two sons, George Junior and Corbell, however, Corbell died at age 7 during the measles epidemic.

In this letter, written in April 1863, Pickett pleads with Sally to come marry him in camp, despite the social improprieties of a woman doing so.

“You know that I love you with a devotion that absorbs all else—a devotion so divine that when in dreams I see you it is as something too pure and sacred for mortal touch. If I am spared, my dear, all my life shall be devoted to making you happy, to keeping all that would hurt you far from you, to making all that is good come near you.”

Unfortunately, poor Pickett was destined for disappointment. Sally writes in a postscript to this letter in the book “The Heart of a Soldier” that she turned “her soldier” down because of the impropriety of such an endeavor.

“So, though my heart responded to the call, what could I do but adhere to the social laws, more formidable than were ever the majestic canons of the Ecclesiastes? My Soldier admitted that I was right, and we agreed to await a more favorable time.”

She did eventually relent and marry “her soldier” later on during the war. In July 1863, she received this note from the general.

“…Now, I go; but remember always that I love you with all my heart and soul, with every fiber of my being; that now and forever I am yours—yours, my beloved. It is almost three o’clock. My soul reaches out to yours—my prayers. I’ll keep up a skookum tumtum [Chinook for strong heart] for Virginia and for you, my darling.” - Your Soldier (July 3, 1863 Gettysburg)

Note: You may recognize the date—the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg, and the time—shortly before the ill-fated Pickett’s Charge. The artillery bombardment, the largest in North American history, began at 1 p.m. and was still taking place as he wrote. (And we say we are “too busy” to write love letters to our spouses today).

George Pickett died 10 years after the war at the age of 50, and is buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Va. La Salle lived until 1931. It was her dying wish to be buried with her husband, but the authorities refused because Hollywood was a military cemetery. Consequently, her body was cremated and her ashes kept at the Arlington Mausoleum. It took another 123 years, but on March 21, 1998, La Salle’s ashes were laid to rest in Hollywood, beside her husband’s grave.

She finally joined the only man she ever loved.

General J.E.B. Stuart

Perhaps one of the most recognizable—and most romantic—figures during the Civil was 28-year-old Brig. Gen. James Ewell Brown Stuart. He first met 25-year-old Laura Ratcliffe at Camp Qui Vive when she was helping to nurse injured soldiers at the cavalry’s winter quarters near Fairfax Courthouse in 1862.

Ratcliffe was the daughter of a prominent Fairfax family, and was living near Frying Pan Church at the time. General Stuart was a married man, but the following letter shows a bit of an infatuation with Miss Laura.

“Camp Laura (March 17, 1862)

My Dear Laura,

I have thought of you long and anxiously since my last tidings from you... I could not counsel you to leave your mother, but if you for any cause make up your mind to leave Frying Pan and will find your way to our lines, I will provide you a home and take good care of you.

You will no doubt find opportunities to send me an occasional note, I need not say how much it will be prized—don’t you know. Have it well secreted and let it tell me your thoughts, freely and without reserve. Can I ever forget that [words scratched out], never to be forgotten good-bye? Will you forget it? Will you forget me? I am vain enough Laura to be flattered with the hope that you are among the few of mankind that neither time, place or circumstances can alter—that your regard, which I so dearly prize, will not wane with yon moon that saw our last parting, but endures to the end. That whatever betides me in this eventful year, you will in the corner of that heart so full of noble impulses, find a place in which to stow away from worldly view the “young Brigadier.”

I do not wish you destroy this, but keep it and take it out occasionally to remember the thoughts and sentiments of “the absent one.”

If you knew how I would prize a letter you would write me every opportunity. Have you forgotten?

J.E.B.”

Ratcliff was more than a pretty companion and a romantic obsession. She served Stuart and the Confederacy in significant ways, putting her life on the line by delivering valuable military intelligence. Upon her death, letters and poems were found in a leather-bound album that Stuart had presented to her sometime in 1862.

Here is a small portion of one of the poems Stuart wrote to her.

“To Laura

We met by chance, yet in that ‘ventful chance

The mystic web of destiny was woven.

I saw thee soothe the soldier’s aching brow

And ardent wished his lot were mine

To be caressed with care like thine…

And when this page shall meet your glance

Forget not him, you met by chance.

March 3, 1862 J.E.B”

General Stuart was wounded on May 11, 1864, at the Battle of Yellow Tavern.

He died the next day in Richmond.

I hope you enjoyed this short sample of letters. Now get your pen out and write your loved one the perfect Valentine’s Day message!

Don’t miss next week’s post on a Confederate spy who fell in love with (and married) her Yankee jailer during the Civil War. (Yes, another romantic story for Valentine’s Day)!